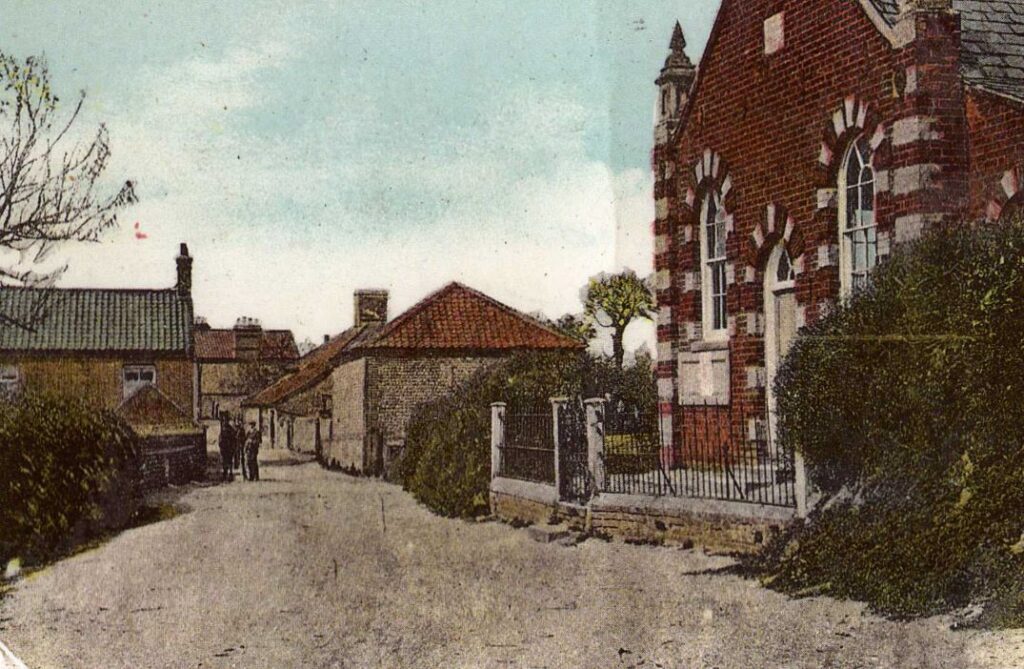

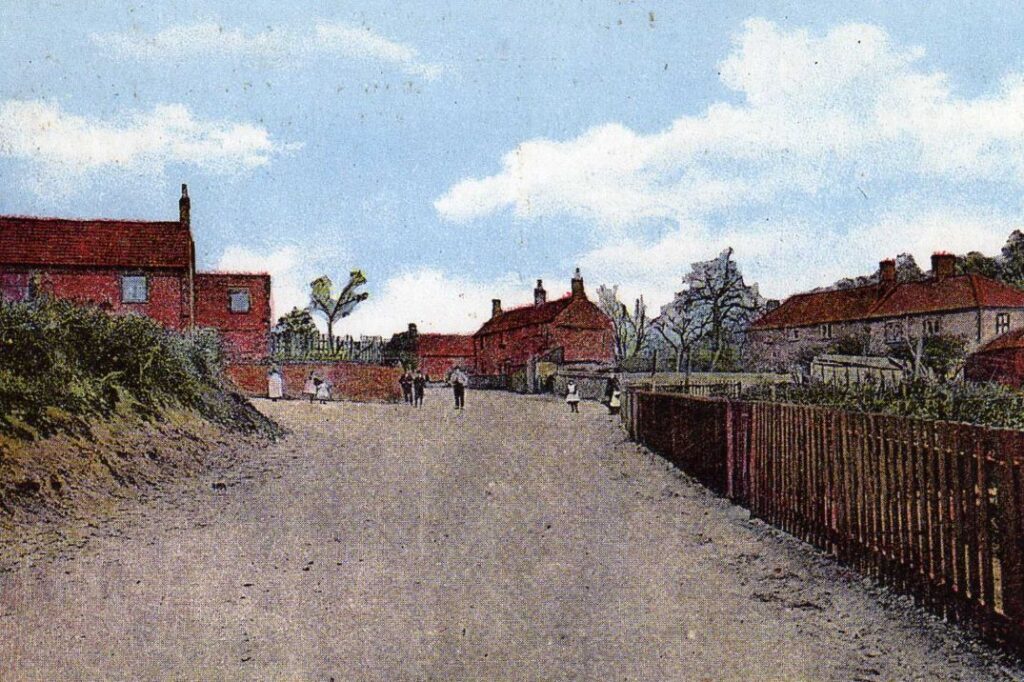

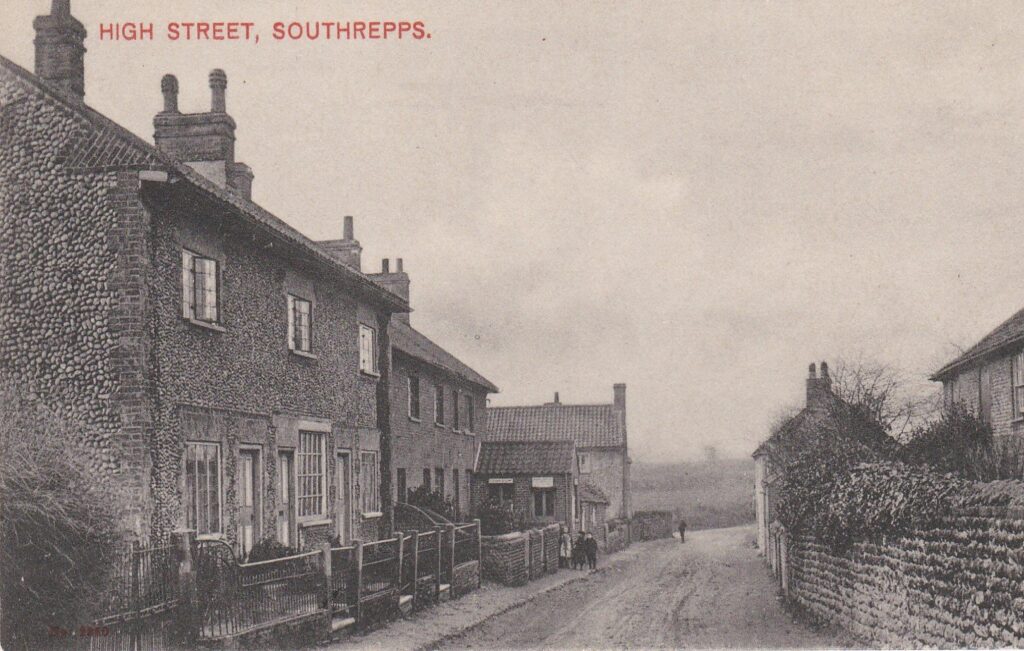

Southrepps is a small North Norfolk village of around 800 inhabitants, situated a few miles south of Cromer. The name Southrepps is probably derived from the middle English “reppes” meaning strips of land. The village lies in two parts called Upper and Lower Street separated by a mile of arable farmland. Upper Street was and remains the social and commercial centre of the village with a large mediaeval Church, Village Hall, Public House and Shop. Part of the centre is designated a Conservation Zone. Lower Street includes an extensive area of woodland and an important Common and Wetland Nature Reserve. There is also a School and a Social Club.

Fields of intensively farmed arable land now dominate the landscape around the village but very few residents now have any direct involvement with the activities on the land. In the village many of the houses both old and new are partially occupied either as holiday lets or second homes. A significant proportion of the permanent residents are retirees or younger incomers working from home or commuting out of the village. Over centuries the population of the village has not changed dramatically but there have been relentless changes to the social and economic life of the village, especially so during the last century. Changes recalled by many of the older residents whose stories and artifacts are preserved in the Southrepps History Hub.

The earliest evidence of the occupation of this part of East Anglia by the predecessors of modern man is found along the shoreline towards Happisburgh a few miles from the village part of The Deep History Coast, with foot imprints dating back some 800,000 years. This pre-dates the later glacial events that created the spectacular eroding cliffs and rolling hills of the Cromer Ridge.

A recent report on an archaeological field walking survey of the parish undertaken as a project by the Southrepps Society has confirmed that Southrepps’s fertile and well drained soils were visited by hunter gatherers migrating across the now submerged Doggerland in Palaeolithic times.

There is evidence that farmers first settled on the higher ground towards the river Mun and there is much evidence of settlements within the parish throughout the Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age. The lost and extant ancient lanes and tracks in the area may well have originated from those times.

Evidence of Roman era settlement is widespread across the village and is confirmed by finds of pottery, coins and in crop marks seen on aerial photographs and satellite images, some of which suggest Roman era field boundaries and settlement enclosures.

Evidence of Anglo-Saxon settlement and trading activity is elusive in the village, with a scattering of finds some close to Roman settlements. It is likely that Southrepps church was built on the site of an earlier Saxon church.

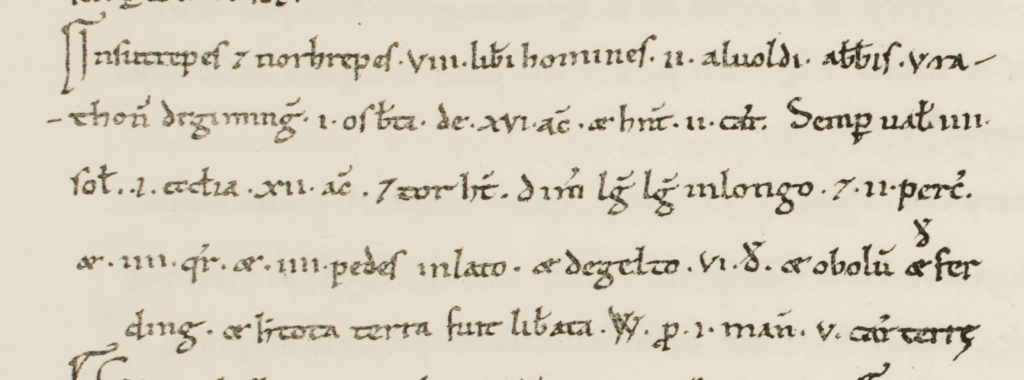

Prior to the Norman conquest in 1066 Southrepps was part of an important jurisdictional area the origins of which are probably of Viking origin. The conglomeration of 8 settlements amounting to some 9500 acres was known as the Soke of Gimingham. The Soke comprised Gimingham, Knapton Mundesley, Northrepps, Southrepps, Sidestrand, Trimingham and Trunch.

Southrepps is recorded in the Domesday Book.

This image is by permission of the http://opendomesday.org/ at this excellent website you can read the English translation. Prior to 1066 the over lords were Osbert; Rathi of Gimingham ; Abbot Alwold (of Holme)

Southrepps and the lands of the Soke together with much land in Norfolk and Sussex was settled on William de Warenne in 1066. William is known to be one of the French noblemen who fought alongside William the Conqueror at Hastings. In Norfolk he held 139 Manors. At Gimingham a Lord’s residence and a Manor Court was established and a Lord’s Hunting Park was created covering parts of Southrepps. Field names on the 1839 Southrepps Tythe Map reference those which were part of the former Royal Park. Subsequently through succession, the Soke was inherited by the Duke of Lancaster. The Soke of Gimingham-Lancaster passed to John of Gaunt and ultimately to the Crown. To this day the appointment of the Rector of Southrepps church is an appointee of the Duchy of Lancaster and is approved by the Crown.

The manorial system much refined by the Normans assigned tiered titles, rights and obligations to tenants of the land. There were at least two manors in Southrepps. The principal manor in Southrepps was originally held by the de Reppes family as a parcel of the Soke and the minor manor was Southrepps Brusyard which included lands (medieval strips) in Southrepps and the surrounding villages and the income from these lands was assigned to the Abbess of the Convent of Poor Claires at Brusyard (now Bruisyard) in Suffolk. Both manors were ultimately held by the Lords Suffield. The Lordship of the manor of Brusyard was acquired by the late Peter Sladden of Southrepps Hall.

The people of Southrepps have a reputation for dissent and there are records of villagers’ participation in violent events during the Peasants Revolt of 1381. Since Elizabethan times there has been a non-conformist meeting place in open fields outside the village. This site now known as the Chapel Yard is owned in trust by the Southrepps Society. Farm workers from Southrepps were in more recent times supporters of the foundation in North Walsham of the National Union of Agricultural Workers and participated in the Great Strike of 1923 which resulted in changes to the laws relating to the employment and wages of farm workers.

The ownership of the Southrepps’s land and property has changed over time. In the 17th and 18th century the Harbord family (later the Lords Suffield) created the Gunton Estate which ultimately owned most of the farms and properties in Southrepps and the surrounding villages including Cromer. The Suffields were perceived as benefactors to the people of Southrepps having built and sponsored the school and donated large parcels of land for allotments. Most recently they gave the Southrepps Common to the village. In the 19th century families with banking interests including the Gurneys, Hoares, and Buxtons acquired large sporting and farming estates in this part of North Norfolk including much of the farmland in the village. Many of these properties was sold off by auction in the early part of the 20th century before and after the First World War. These sales, forced in part by agricultural depression and the consequences of the Great War included the break up of much of the extensive Gunton Estate including farms and property in Southrepps. Most of the former estate farms in Southrepps were purchased by the tenants including the Tylers of Hall farm, the Bartrams of Church farm and Wellspring farm and Charles Learner of Hill House farm.

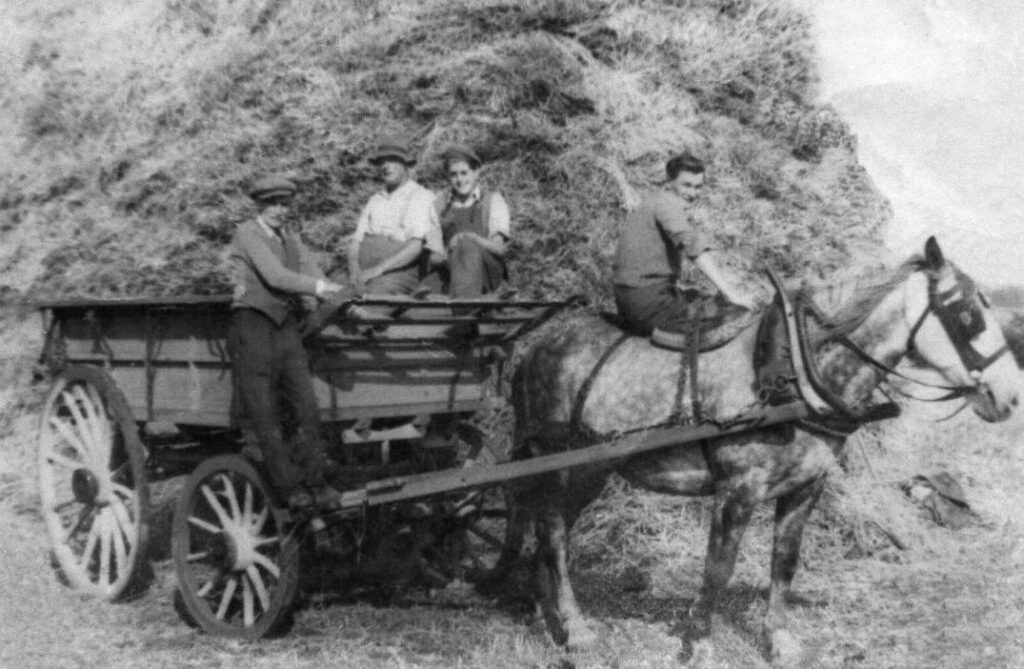

At this time (2024) there are few who can still recall life in the village in the inter war period and through to the 1950s. During those times the village changed dramatically. For decades the village had been a nearly self-sufficient community of often closely related agricultural workers, farming related businesses, shops, three public houses, a social club and reading room, a church and two chapels and a large and thriving school. There was a total reliance upon the horse for transport and heavy work on the farm and most of the residents including wives and children found work and income on the farms. By the late 1950s tractors had replaced the horses, cars and buses plied the streets and many redundant farm workers travelled daily to work in well paid jobs in the new canning and lorry trailer factories in North Walsham.

By the mid-20th century some of the Southrepps farms had been acquired by the East Anglian Real Property Company, a Dutch-owned farming company set up by the founders of the beet sugar factory at Cantley. They owned and directly managed numerous farms across the county including a large farm at Paston. The intensive and innovative Dutch methods of farming changed the landscape of large parts of the village by removing hedge rows and trees to create large open fields. In the latter part of the century the EARPC portfolio of farms was sold to the National Coal Board Pension Fund who shortly after sold the entire estate. The Southrepps farm was purchased by Peter Sladden in 1980s. Peter Sladden initiated a masterplan to recover many of the lost wooded features and hedges and hundreds of trees were planted. Avenues of trees have individually recorded dedications to village residents and their children, Peter’s family and friends and those that lost their lives in the two world wars.