Author: Chris Shaw

The arrival of American forces in 1942 to the UK brought many changes to British life as well as a big boost to the war effort.

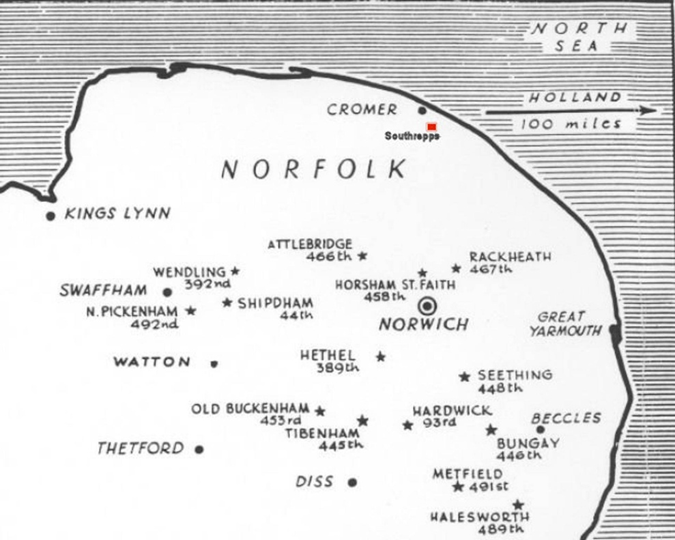

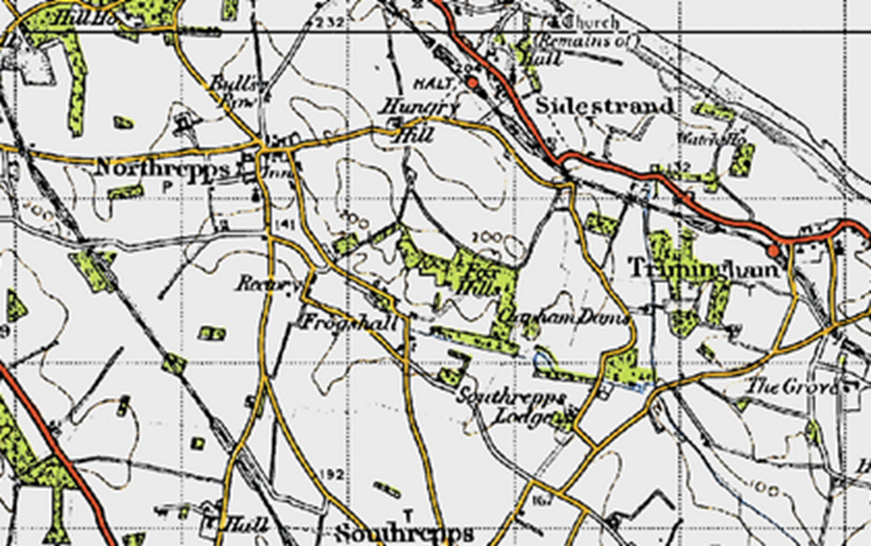

East Anglia, being relatively close to continental Europe, became the home for the United States Army Air Force (USAAF). Many new bomber bases were constructed as can be seen on the map below.

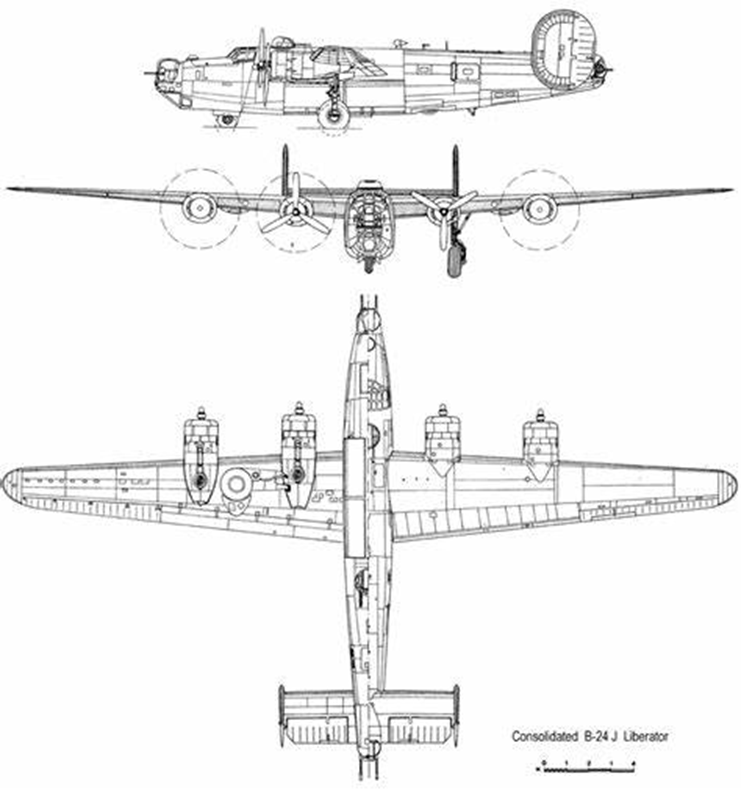

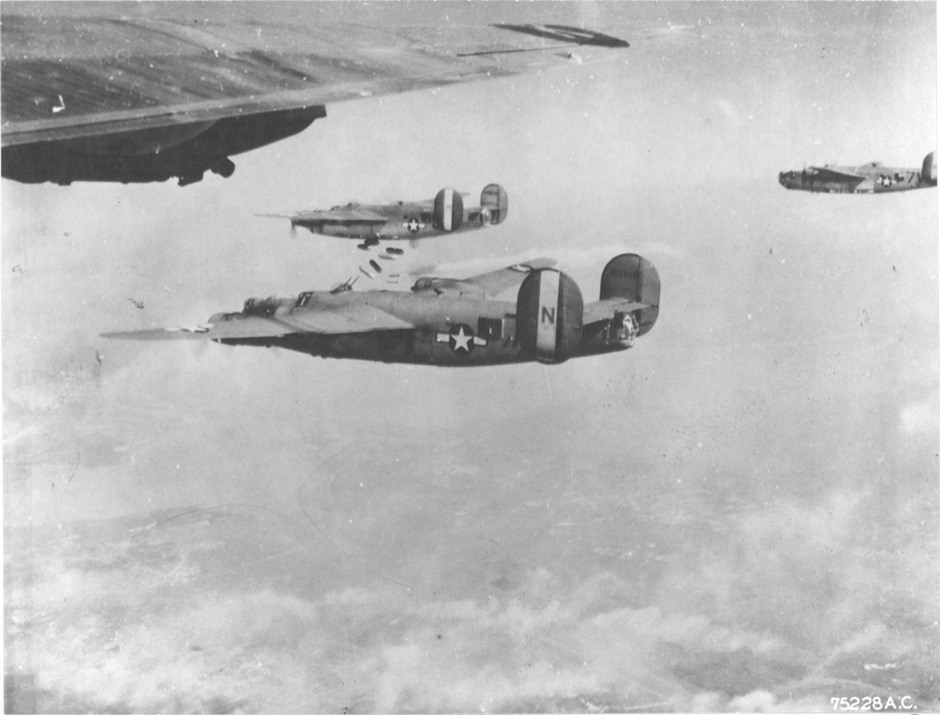

A number of different aircraft were introduced with the Consolidated B-24 Liberator being one of the most familiar ones. The aircraft carried a crew of 10.

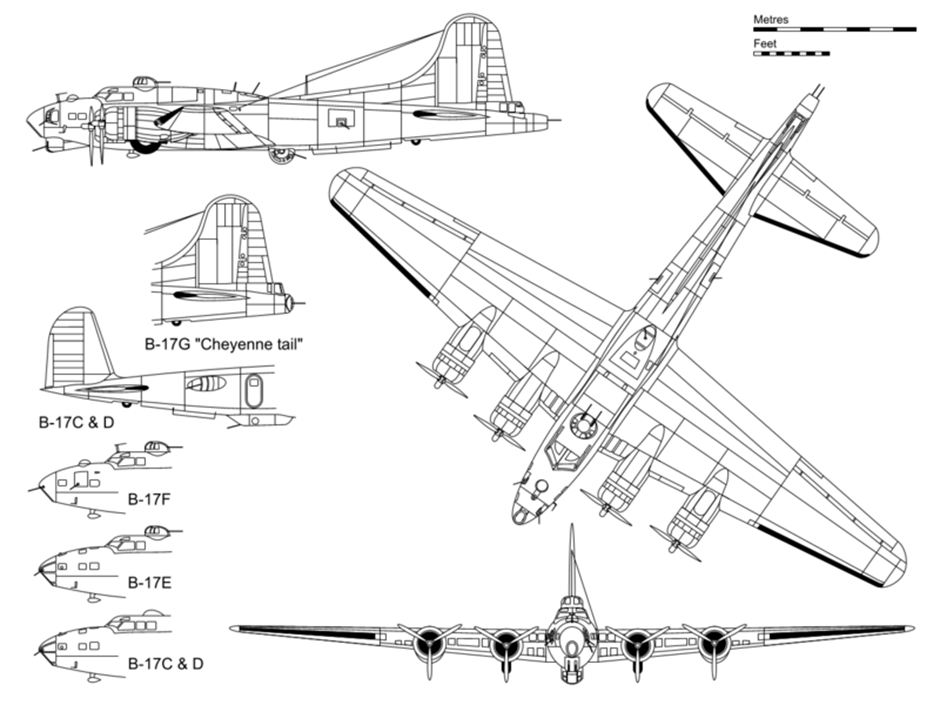

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was also a familiar sight in the skies of East Anglia.

The Flying Fortress also carried a crew of 10.

A number of aircraft from the British and American air forces crashed around our village during the Second World War and we record below their bravery and sacrifice.

20th November 1940

RAF Handley Page HP.52 Hampden X3023

The Handley Page HP.52 Hampden was a British twin-engine medium bomber of the Royal Air Force. The Hampden was often referred to by aircrews as the “Flying Suitcase” because of its cramped crew conditions.

The aircraft departed RAF Waddington on an operation to Lutzkendorf. While returning to base, the crew encountered very bad weather conditions and the airplane crashed near Templewood.

Three of the four crew were killed in the accident. The casualties were Sgt Jack Leonard Frederick Ottoway (pilot), P/O Archie Ronald Kerr (navigator) and Sgt Stanley Frederick Elliot (wireless operator). Sgt Stanley Hird was injured in the accident.

13th November 1943

USAAF Consolidated B-24 Liberator 41-29168

The aircraft was based at Shipdham with the 44th Bomber Group and was returning from a raid on Bremen in Germany during which it received battle damage.

Fortunately it was out of fuel when it crash landed near Frogshall Farm.

On that day Derick Grey and two or three other boys were near Lands Pit by the Church. They saw the plane flying low heading eastwards, probably trying to ditch in the sea at Sidestrand, but it fell short and crashed into a Kale field.

It skidded across the field, over the Northrepps Road and ended up by Two Gates Lane. As it crossed the road, the wingtip hit a lady cycling along the road. Do we know who the lady was and did she recover from her injuries?

First on the scene was Peter Drury, the local baker (the bakery and shop was in Chapel Street, Upper Street). He administered first aid to the cyclist and probably saved her life as she was badly hurt.

One member of the crew, navigator 1st Lieut F L Jope, was trapped beneath the damaged plane and two local men, William Risebrow and Jimmy Fox dug a pit beneath the plane to free the injured man. They received a letter of commendation from Brigadier General Walter R Peck for saving the life of this seriously injured airman.

Compiled from information in the 44th BG archive, ‘Over Here’ by Stephen Snelling and the late Derick Grey.

April 1944

USAAF Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress ?

An aircraft crashed to the east of Claughton Pellew’s house (now known as Wedgewood). It crash landed on the Trunch road and then collided with a large Ash tree. It may have been part of the 457th Bomb Group.

Can anyone help with further information?

8th April 1944

USAAF Consolidated B-24 Liberator 42-73505

The aircraft and crew were based at RAF Wendling and were taking part in a raid in Germany. Problems with the aircraft resulted in an attempted return to base. The report below provides the details.

The Report of Aircraft Accident contains this sequence of events based on statements made by engineer S/Sgt Charles T. Cook and right waist gunner Cpl George T. Shikenjanski:

“After having reached a point three or four miles beyond the Enemy coast the oil pressure of No. 1 engine fell to a very low level and oil was noticed to be leaking from the engine. The prop was feathered with difficulty. Almost immediately the oil pressure on No. 2 engine dropped very low and efforts to feather the prop failed.

During this short period the plane turned back toward land, the bombs were jettisoned into the English Channel and all excess weight including the guns were thrown overboard. The men in the waist took up ‘Ditching positions’ and the plane crashed just after reaching the coast at approximately 1320 hours at Bizewell Farm, Sidestrand, Norfolk.

Shortly after crashing the plane caught fire and burned. 2/Lt Leland, S/Sgt Cook, T/Sgt Marshall, Cpl Shikenjanski, and Sgt Sullivan were all injured in the crash.”

The responsibility for the crash was deemed “100% material failure.”

Michael Emmons was a young eyewitness in Sidestrand. A 7-year old, he had been playing in the road outside the Council Houses learning to ride his new bicycle with the help of Peter Dix who lived at No. 1 the Council Houses. The unfamiliar noise from the B-24 caught their attention. As the B-24 approached from seaward, they noticed that only two of the four propellers were turning. They both watched as the stricken Fairy Belle flew low over Sidestrand Church, banked to the left, and passed close behind the Council Houses. Then, it lost height and the boys heard it crash near Bizewell Farm at approximately 1:10 pm.

A number of villagers rushed to the crashed Liberator. At least three ladies tended to the five American airmen who had managed to escape from the wreckage. Ruby Royall (who lived at Garden Cottage), Dorothy Chadwick (from The Cottage) and Ida Henden (from Windy Ridge) were designated as First-Aiders, having been trained by the Red Cross and all members of the organization.

Dorothy Chadwick, who heard the crash, grabbed her first-aid bag and was about to get on her bicycle when she was spotted by a Military Police motorcyclist, probably stationed at Sidestrand Hall. Dorothy abandoned her bike, boarded the pillion of the motorcycle, and was probably the first of the three first-aiders to arrive.

Charlie Royall, acting as village ‘special constable’ attended the scene with John Bullimore. It is believed that Charlie and John entered the burning plane and it was they that laid out the deceased who are listed below.

2/Lt Thomas Lavar Anderson (Pilot) born 2nd August 1921, buried Evergreen Cemetery, Springville, Utah County, Utah.

2/Lt James Jacobs (Navigator), buried Elmwood Cemetery and Mausoleum, River Grove, Cook County, Illinois.

Staff Sgt Elmer Schmidt (Turret Gunner), buried American Cemetery, Cambridge.

Sgt Robert M Vandervort (Gunner) born 31st March 1923, buried Bedford Cemetery, Monon, White County, Indiana.

Sgt Earl B Richards Jr, no further details known.

Compiled from information in 392nd Bomb Group, HonorStates.org and Air Britain.

6th June 1944 (D-Day)

USAAF Consolidated B-24 Liberator 44-40247

Liberator 44-40247 ‘Shoot Fritz, You’ve had it’ of 389th Bomb Group took off from RAF Hethel shortly after midnight to support the D-Day assault.

At around 2.25am the aircraft went out of control and crashed near Pond Farm in Sidestrand, all 10 crew members were killed.

Details of the crew are listed below:

1/LT Marcus Vincent Courtney (Pilot), born 4 May 1921, of Charlotte, Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Buried at the American Cemetery, Cambridge.

1/LT Carl Earl Crouse (Navigator), born 3 May 1921, of Los Angeles, Los Angeles County, California. Buried at the American Cemetery, Cambridge.

1/LT Lowell Russell Brumley, born 10 November 1920, of Burleson, Johnson County, Texas. Buried at the American Cemetery, Cambridge.

Staff Sergeant Earle D Elliot (Right Waist Gunner), born 21 January 1923 of Walhalla, Oconee County, South Carolina. Buried at West View Memorial Cemetery, Walhalla, Oconee County, South Carolina.

Captain Everal Anthony Guimond (Bombardier), born 20 August 1915 of Manteno, Kankakee County, Illinois. Buried at the American Cemetery, Cambridge.

Staff Sergeant Stephen R Sosneckne (Tail Gunner), born 1 February 1923, of Islip, Suffolk County, New York. Buried at Long Island National Cemetery, East Farmingdale, Suffolk County, New York.

Staff Sergeant Gene Foster Cornell (Left Waist Gunner), born 21 August 1921, of Plymouth, Richland County, Ohio. Buried at Greenlawn Cemetery, Plymouth, Richland County, Ohio.

Staff Sergeant Harold F Leggett (Ball Turret Gunner), born 5 September 1923, of Boston, Suffolk County, Massachusetts. Buried at Long Island National Cemetery, East Farmingdale, Suffolk County, New York.

Technical Sergeant Francis Guillory (Top Turret Gunner), born 14 March 1911, of Eunice, St Landry County, Louisiana. Buried at Saint Paul Cemetery, Eunice, St Landry County, Louisiana.

Technical Sergeant William C Harris (Radio Operator), born 12 September 1916, of Birmingham, Jefferson County, Alabama. Buried at Oakland Cemetery, Birmingham, Jefferson County, Alabama. Married to Thelma D Harris.

Compiled from information provided by Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives, HonorStates.org and the late Derick Grey.

28th June 1944

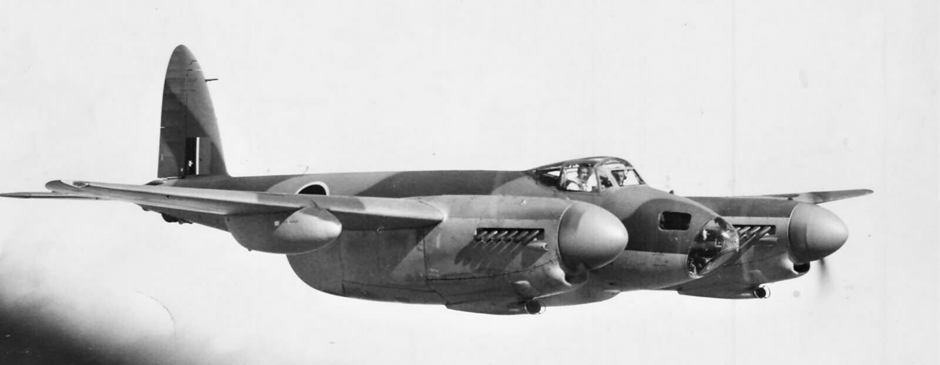

RAF De Havilland Mosquito IX ML909

Mosquito ML909 of 139 (Jamaica) Squadron took off from RAF Upwood, Huntingdonshire for a training flight but lost engine power and crash landed in Antingham. The occupants, Flight Officers Thomas Dickinson and Eric Keith Martin, survived the crash but had some injuries.

Compiled from information in flightsafety.org and Air Britain.

7th October 1944

USAAF Consolidated B-24 Liberator 41-29340

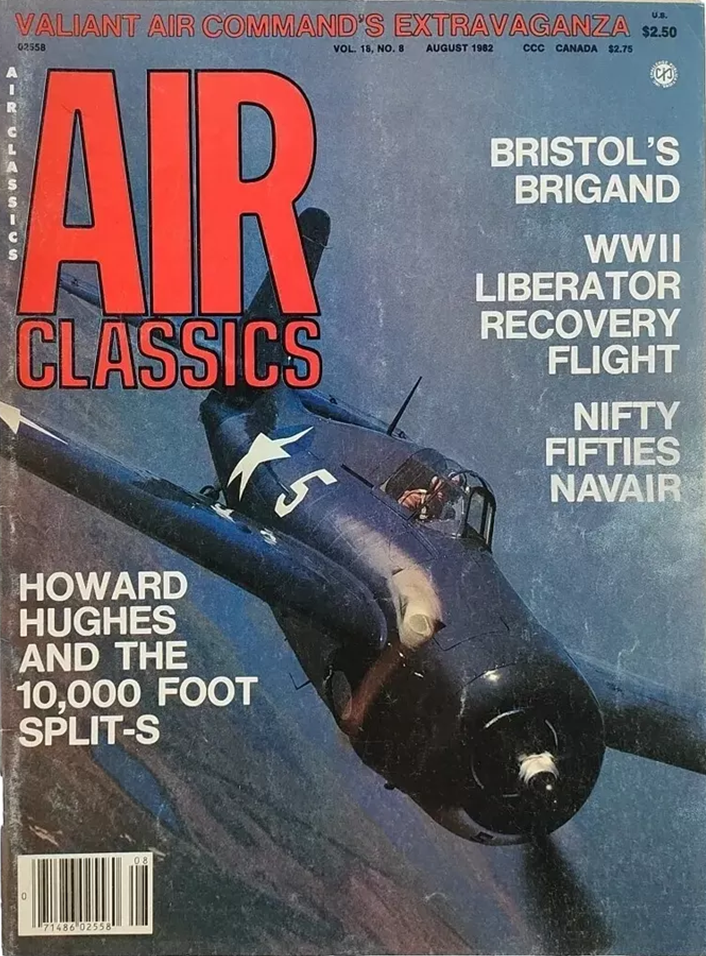

‘Yankee Buzz Bomb‘ made a forced landing in a Southrepps barley field just off Long Lane on 7th October 1944. The magazine article below provides the details of the landing and the recovery.

Cloistered Cockpit by George A Reynolds

Recovering a battle-damaged Liberator from a British farm field was no easy task

The article from the August 1982 copy of Air Classics is reproduced in full below –

“To most Americans, World War Two has become an era of the past – serving mostly as a milepost in time. But the survivors, those sixteen million citizens comprising our armed forces during that war, still consider it the epitome of the good old days or extinct tribulation. For it created, in each of them, enduring mementos of romance, suffering, blood and fire, goldbricking, destruction of specifically, ‘that day I almost bought the farm.’ The latter typifies yesteryear’s airmen in the grandeur of an air force that was ‘the Mighty Eighth.’

Today, ex-Captain Tommy L. Land of Memphis, Tennessee, recalls that time vividly. ‘It was autumn 1944, in England and tools of war were changing. The familiar Olive Drab colour of B-24’s I flew was giving way to a bare look of bright aluminium and especially garishly painted tail sections. This identified one airplane among many as belonging to a particular bombardment group.’

As vari-coloured planes began arriving for major repairs at the 3rd Strategic Air Depot (SAD) field near Watton, those of us assigned this support duty paid little attention to the colours or their purpose. Nor did I realize how important some bright red ovals with a vertical white stripe would become to me in the near future.

On 7 October, Liberator #41-29340 (Yankee Buzz Bomb) was in a flight of twenty-nine B-24’s over the North Sea enroute to bomb the Rothensee oil refinery at Magdeburg, Germany, when it lost two engines and turned back to England. Then its bombs were accidentally salvoed through the bomb bay doors, setting up tremendous drag. It reached the English coast however, and her pilot, Lt Albert H Grice ordered seven crewmen to bail out. He and co-pilot Neil A. J. Peters and the flight engineer remained aboard to save the aircraft.

(The co-pilot was actually 2Lt Clifford G Peters. Lt Neil AJ Peters was KIA in March 1944 when he and his crew ditched in the Channel. One man from the Grice crew, Sgt Edward J. Mire, was killed when his parachute failed to open)

They chose an emergency strip about four miles southeast of Cromer in a split second decision. It was a narrow, level barley field running north-south with a tall power line at the north (end), a deeply eroded ditch on the south (end) and trees at either side. But they landed safely.

Later Captain A. R. Ayers of Bement, Illinois, inspected the damaged bomber for the 3rd SAD Mobile Repair Group and determined that it was repairable. Disassembly for removal was impractical because of huge labour and time factor involved. So, I went to the site to see if the airplane could be flown out.

Normally a B-24 used about 4,000 feet of runway for takeoff. Here there was only 1,500 feet available – sod at that!! But heavy bombers were in critically short supply and our job was to repair cripples for return to combat service.

A second look at the strip convinced me, with proper wind and humidity conditions, the fly-out could be made. Back at Watton, I told the maintenance chief, Major Lee Witzenburg of New York City, of my findings. He said, ‘Okay, Tom, you fly ‘er out and I’ll go along as flight engineer.’

Next a crew from the 46th Mobile Repair Squadron, headed by Sergeant Harry Mundy of Rockridge, Ohio, was sent to make temporary repairs so the aircraft could be ferried to Watton for a major overhaul. To make the short field takeoff, removal of armament, radio gear and all other nonessential equipment was required. Only twenty minutes of fuel for the forty-mile flight was left aboard, and the crew was restricted to three men as further weight limitations.

It rained, English style, until the fairly stable field became a quagmire of mud. Then, an engineering battalion assembled a 1,400 foot steel mesh runway. But it didn’t work. Under the plane’s weight, the panels sank right into the mud. Ah. Yankee ingenuity! After the matting was reassembled over a bed of straw, the problem was solved. Now we could only wait for a strong south wind and very heavy humidity for maximum lift.

Sergeant Mundy’s crew worked diligently in getting the ship airworthy. The rest of us went about normal assignments, awaiting those ideal atmospheric conditions. We all knew the absolute necessity of having the ultimate in power on take-off to get the bomber over that awesome ditch at the runway’s end.

D-Day came on 17 November. Weather was poor over southern England, and combat aviation activity was completely grounded.

In the early afternoon, Base Weather verified high humidity and predicted a stiff wind would hold until nightfall. But the ceiling was only 300 feet and visibility hovered around one mile. These would drop to zero-zero with darkness. My co-pilot, Captain Henry Miller of Mt. Kisco, New York, the major and I discussed the situation and the likelihood of a much longer delay, then decided to go ahead. We left for Cromer by jeep because there was no chance of flying into the field with our ‘baby’ occupying the only runway.

When we arrived at the site, much later than planned, the mobile crew was exuberant. Excitement over the project was flowing in everyone. The air was literally oozing moisture as a light mist, so common to the United Kingdom, and that southern breeze was holding. But the delay in getting there, a final check of the plane and rechecking with Base Weather extended the take-off time. We needed no surprises in weather or darkness at Watton. I phoned from a farmhouse, and the forecaster told me that present conditions were expected to hold another thirty minutes at least.

As the engines coughed to life, I looked at Henry and Major Witzenburg. They were ready, the kite was ready. Those four turbo-charged Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engines were howling under full throttle. Baby jiggled like a hula dancer on the steel (matting), quaking against locked brakes. When I released her with propeller pitch full bore, and half flaps, she virtually leapt into a take-off run.

We roared down the strip and at the precise moment, Henry dropped full flaps to balloon the ship from the matting, at the 1,200-foot point, and over the gully.

The ditch zipped under, we were airborne! Gear up, don’t sink! She didn’t. That gawky bird on the ground moments ago climbed like a homesick angel, steadfast and gracefully. Southward to Watton now.

In our jubilation over a successful take-off, we hardly noticed an airbase slip under the left wing a few minutes afterward. But our 300-foot altitude carried us within close range of the 466th Bombardment Group in Attlebridge.

The ceiling began lowering and visibility dropped to almost nil in the misty sky. It was getting dark and, near Watton, the elements grew even worse. There were no navigation aids aboard, and we dropped lower to look for our field’s runways. But nothing looked familiar. I was lost and if we flew over the airdrome, none of us saw it.

It was a nauseous feeling. Success was so close, but now! ‘About ten minutes fuel left, Tom, maybe less.’ Major Witzenburg reminded me. No way to ask for help. Perhaps that field we passed is still open. I started a wide turn to the left, retracing our flight path northward. My mind began racing and settled on tactics instructors stressed on me back in flight school. Never, but never, attempt an emergency landing at night in open terrain. Last resort. Set the autopilot on a heading for the sea and bail out. Then another sorely needed bomber will have vanished, but our personnel’s hard work would linger long in the remorse of failure.

While we were pondering the next move, another sweeping left turn brought dim winks below. Many moving, dancing flickers barely visible.

Lights? There shouldn’t be any here, total blackout has been a way of life in the UK for years. Then someone said, ‘We’re over Norwich.’ Barely over it, however, at 200 feet. Flashlights, carried by pedestrians, were reflecting on wet pavement in the city and resembled countless darting fireflies.

At that moment of realization I became petrified. Norwich Cathedral’s spire is jutting up somewhere, 315 feet high. Pull up, get some more altitude fast!! Too late. It just flashed by while we watched. All this in a matter of seconds, but I well remember the unique feeling of simultaneous fear and relief.

What now? I held the gentle left turning course. A single amber light that should not be burning. But we passed one, no doubt, and there stood another on our present, unaccountable heading. I didn’t correct even two degrees. Then a third popped up. We knew it had to be the night approach lane of the 458th Bombardment Group at Horsham St. Faith, just north of Norwich. Those lights were glowing in strict violation of security regulations (without 458th aircraft aloft). Why? How? Who was responsible?

I held my course and began reducing airspeed. The field? No telling how far away it is, and we could only see each light as we passed over. Think, Tom, don’t lose them, I told myself. Be careful, no fouling up now and we’ll get this bird down safely. But I could only do what I was doing. Yet we kept perfectly aligned in the landing pattern, at the correct altitude and were led beautifully by those radiant approach beacons. Check list . . . reduce throttle, lower flaps, increase propeller pitch and gear down.

Lord keep me from a bonehead mistake now. Airspeed? I heard Miller shout, ‘Hell, I can’t even see the instrument panel anymore, let alone the indicator.’ Well, I just played it by ear and the seat of my pants. No matter, our moves were already made when the last approach light slipped under. Full flaps. Airspeed seems okay, no stall warning buzzer yet. I would set her down regardless, there was no chance for a second try.

The feel of the aircraft was perfect as some green lights at the runway’s end cropped up. Then came the cake’s icing – strings of gold plainly marking either side of that precious tarmac. The Lib’s speed and altitude couldn’t have been better if we had followed Consolidated’s technical manual to a tee. She seemed to float onto the field from out of that black wetness to a nose high landing.

We taxied over to the flight line to questions and more questions. Then some missing links began to come for us. When we flew over Attlebridge, they saw us and since no one was supposed to be flying, it caused quite a stir. The tower controller on duty recognized those red and white tail markings on our ship to be from the 458th Bombardment Group. Also, he very alertly surmised our probable encounter with weather and darkness, then assumed we were trying to find Horsham St. Faith.

Our benefactor phoned the 458th control tower to report one of their planes had just passed over and suggested they turn on the approach runway lighting system. It took a good selling job on his part we learned, as the 458th people thought he was ‘flak happy’.

Sergeant Harold Perry of Durham, North Carolina, insisted, ‘I’m positive, none of our aircraft are flying today.’ But after more persuasion, he agreed to switch the lights on for a short time, just in case.

I was a young pilot then, highly trained and finely honed in extraordinary pilotage. Usually, the job was no problem for me. However, against the obstacles the three of us faced that day, all of my qualifications and skills were inadequate for the task. But much to my disbelief and certainly the relief of my crew, we ‘four’ landed safely. Those esteemed flight instructors back at school never once gave an inkling that someday when I least expected, God would be flying with me incognito.”

After being fully repaired Yankee Buzz Bomb resumed operations with 458th Bomb Group and on 15th April 1945 was one of the aircraft used to drop Napalm on German forces in the Gironde estuary area.

It is thought that Yankee Buzz Bomb crashed in Scotland whilst being ferried back to the USA after the war ended, however this is currently unsubstantiated.

On 10th February 2016 the North Norfolk News carried a story from Derick Grey asking for help in contacting the family of Sgt Edward Mire who died after bailing out of the aircraft.

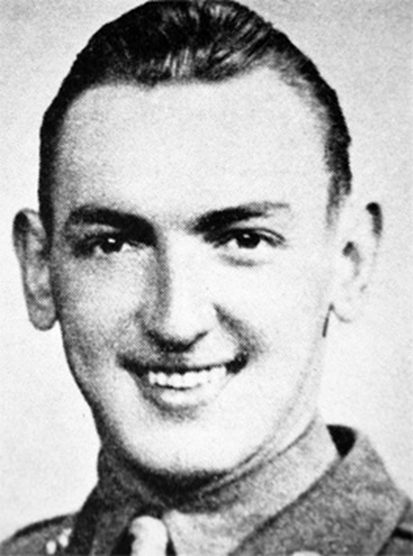

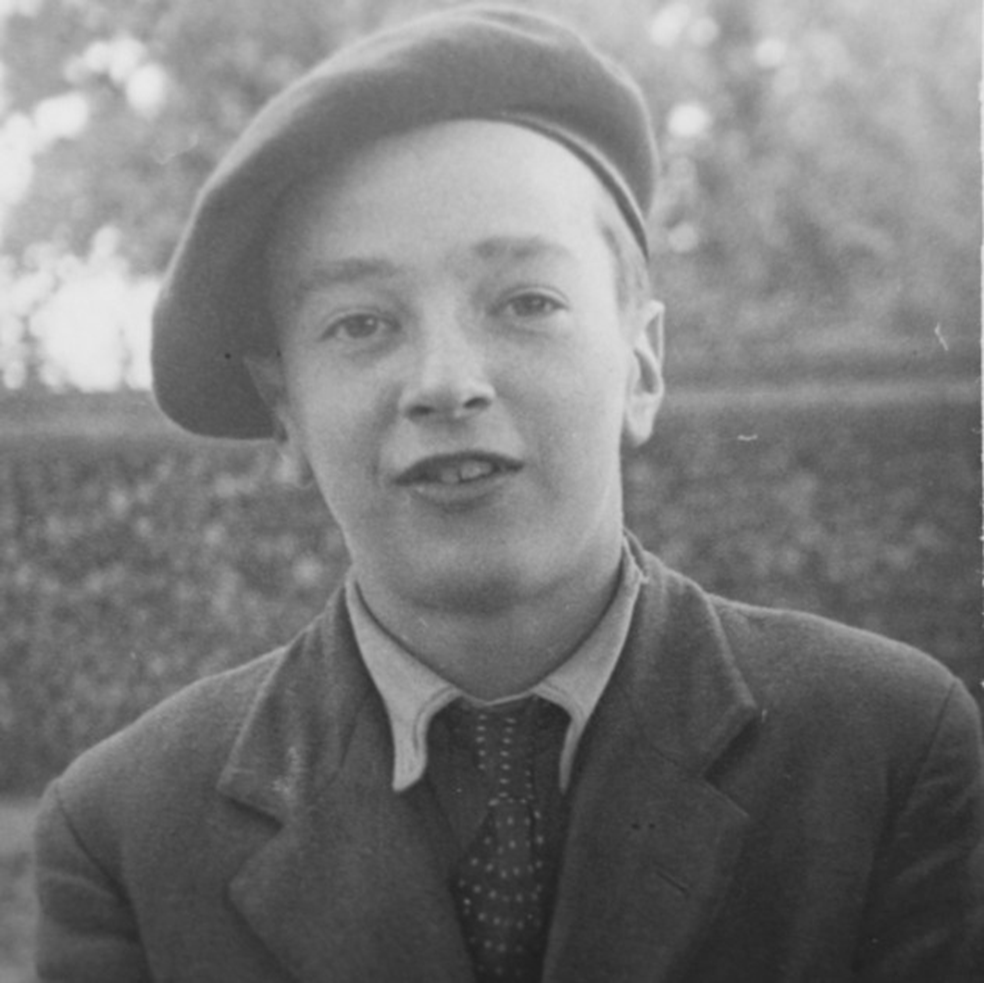

The stricken plane had been seen by Derick (left) and his pals and they rushed to the site just to the east of the Norwich to Cromer railway line. Two crew members were standing on top of the aircraft, a third was safe inside. The Police soon arrived, the area was cordoned off and the children shooed away.

Derick explained that about 20 years ago he had told the story to Peter Sladden, owner of Southrepps Hall. Mr Sladden had established a memorial avenue of trees along Long Lane and was happy to add another one in memory of Sgt Mire.

On 7th April 2016 The Eastern Daily Press reported that following Derick’s earlier request a local man had managed to make contact with Sgt Mire’s family in Louisiana and they sent Derick a letter containing a photograph of Sgt Mire.

On 7th October 2016 (62 years after Sgt Mire lost his life) the village of Southrepps remembered this young American with the dedication of an Oak tree. Canon David Roper, the Rector of Southrepps, led the open-air service which remembered the airman and praised the special relationship which still exists between America and Great Britain.

Standard Bearer Robert Ovenden, chairman of the Mundesley and District branch of the Royal British Legion, led the short parade before dipping the flag for a minute’s silence and 18-year-old Andrew Mitchell, a member of Cromer and Sheringham Brass Band, played the Last Post.

Compiled from information in the 458th BG archive, Eastern Daily Press reports and the late Derick Grey.

10th February 1945

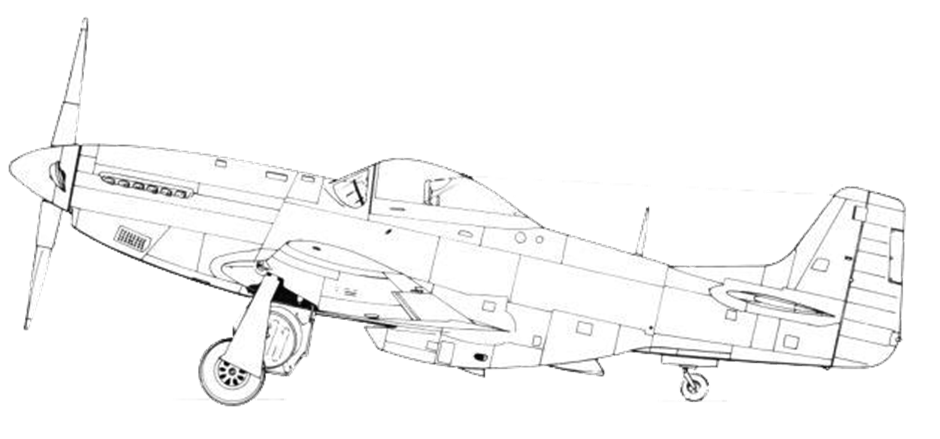

USAAF North American P-51 Mustang 44-14603

The aircraft from 355th FG and based at Steeple Morden in Cambridgeshire suffered from engine failure over North Norfolk and made a forced landing North West of Tyler’s Bridge, Southrepps (Tyler’s Bridge is on Hall Road and carries the road over the railway).

The pilot survived the crash but the aircraft was written off.

Compiled from information provided by flightsafety.org and the late Derick Grey.

Date unknown

RAF Supermarine Spitfire

The aircraft made a forced landing in the 110 acre field North East of Hillhouse Farm and flipped over on landing.

The pilot walked into the village to use the telephone at Williamson’s shop to inform his base.

Does anyone have more information about this incident?

Compiled from information provided by the late Derick Grey.